About

Sensitive instruments have been able to record ever smaller earthquakes in different parts of the world, especially since the 1950s. As the data on these small earthquakes accumulated, two fundamental questions emerged: (i) what are their characteristics and physical properties? and (ii) how do they relate to larger shocks? One of the prime characteristics of small earthquakes is their clustering in space and time, for example, as sequences of foreshocks, aftershocks, and earthquake swarms (Richter 1958; Mei 1960; Bak et al.2002; Baiesi & Paczuski 2004; Zaliapin & Ben-Zion 2013; Gu et al.2013; Moradpour et al.2014; Zhang & Shearer 2016). Aftershocks occur almost universally, as a transient sequence of smaller events occurring after a main shock, at a rate that decays over a few months or years to the background level in the form of an inverse power law known as the Omori–Utsu law (Utsu et al.1995). Swarms are clusters of events in space and time with no clear main shock.

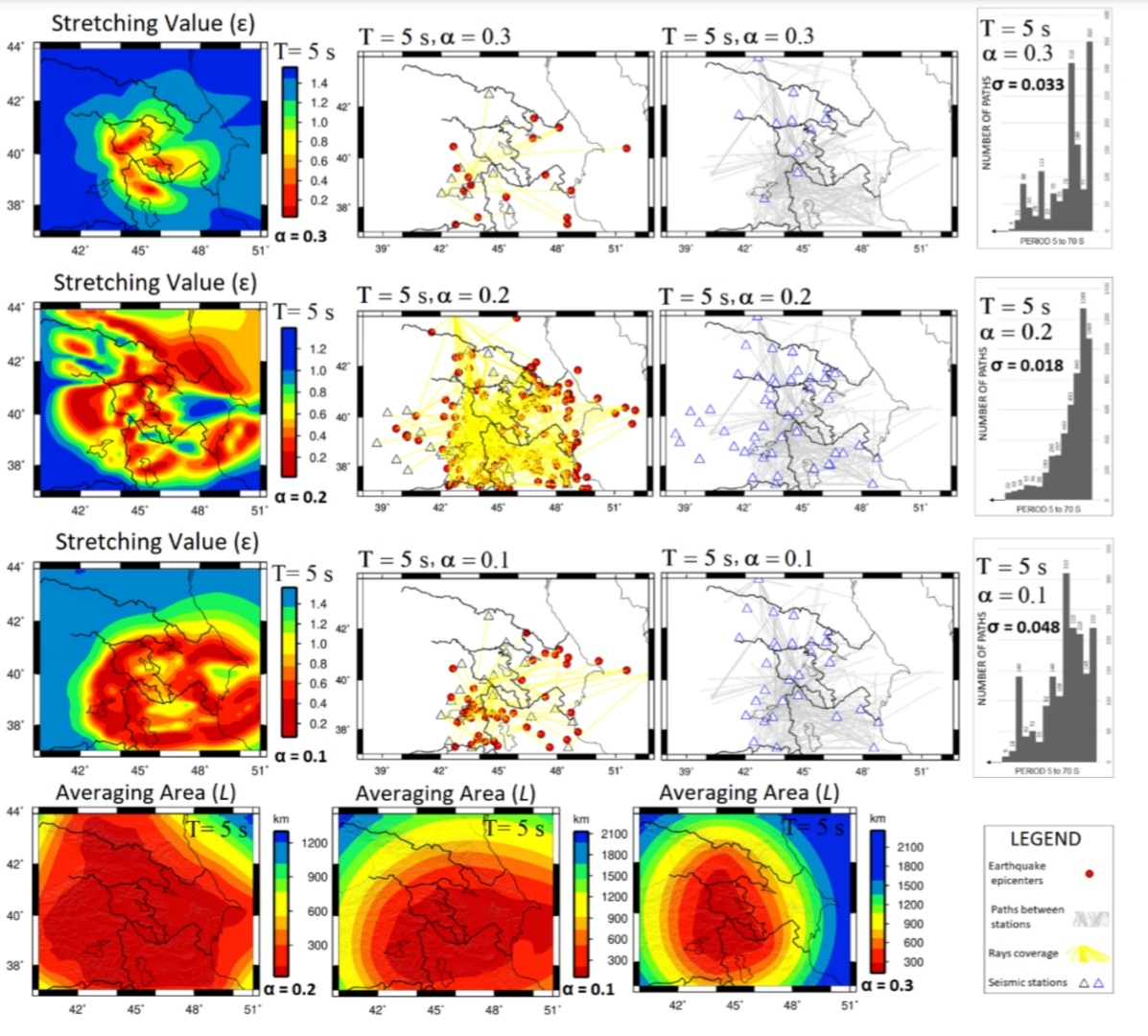

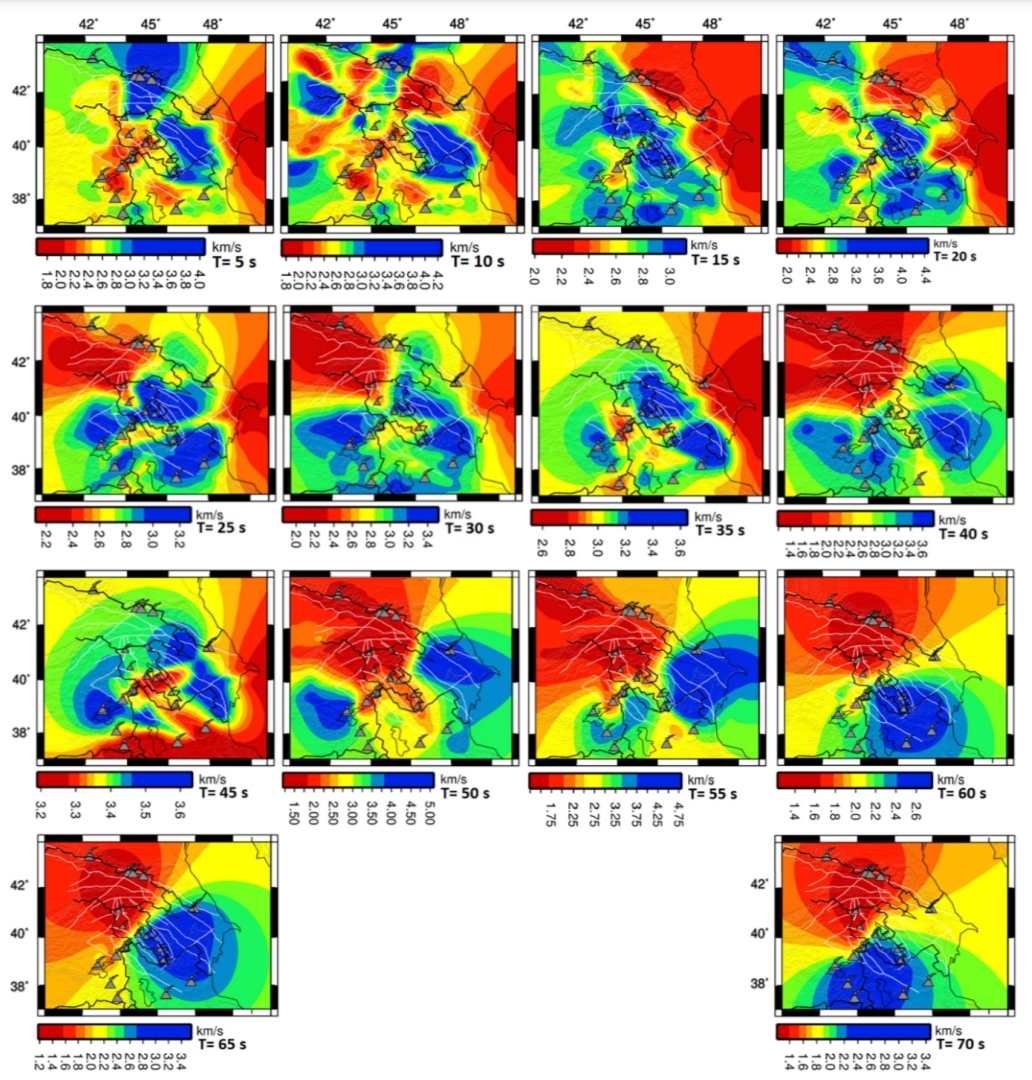

We examine the case for persistent clusters for the case of seismicity around Caucasus. It is a highly densely populated and an important economic region in an intraplate continental setting that has been associated with large historical earthquakes. The region has a rich historical archive that is still being evaluated and updated.